Your donation will support the student journalists of One School of the Arts. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Underrepresented Women in History

March 27, 2023

Edith Bolling Galt Wilson posing for her photo as First Lady of the United States.

According to the English Heritage organization roughly 0.5% of all recorded history is related to women; now considering that approximately 50% of the entire world’s population is made of women something is quite wrong indeed. That the stories of robust and influential women, riveling or even exceeding that of their male counterparts, through centuries old systemic sexism within historical societies, was being dismissed and forgotten. However those who loom greater than life never stay forgotten for long, for while those in power who seek to belittle and lambaste the giants of the world, someone will remember.

Edith Bolling Galt Wilson was the second wife of President Woodrow Wilson and served as the First Lady of the White House from 1915 to 1921. During Wilson’s presidency, he worked on drafting the plans for what would soon become the United Nations. However, when he suffered a stroke in 1919, he became bedridden and paralyzed, making him unable to perform his duties.

Edith Wilson and a close circle of friends kept the president’s condition a secret from the public, and touted his ‘recovery.’ With the president unable to carry out his duties, Edith Wilson stepped into the spotlight and took on the role of a proxy president. According to the Miller Center’s biography of Ms. Wilson, “Although the President was paralyzed and unable to carry out the duties of his office, Edith insisted that he must not resign because she believed that losing office would kill him. This was the single most important decision she made during Wilson’s illness, and from it followed all the rest — her concealment of the severity of his debility from the cabinet and the press, her determination that almost no one be admitted to the sickroom, her screening of the papers and issues that would be brought to his attention, and her assumption of the role of secretary, reporting the President’s decisions to government officials.”

As a result, Edith Wilson became the de facto leader of the executive branch of the government for a time. This was the first time in American history that executive authority fell to a woman, and she led with pride. The responsibility of leading a nation is of great magnitude, with the direction and lives of millions of souls and families lying at the partial discretion of a single person.

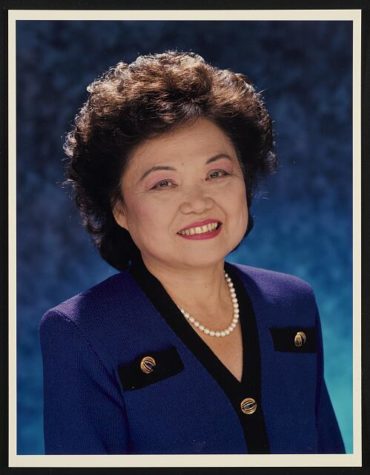

Born on December 6th, 1927, Patsy Mink was born in HamakuaPoko in the Hawaiian territories to a third-generation Japanese family. She was dedicated to politics and civil rights from a young age. In 1944, she attended the University of Hawaii and subsequently the University of Nebraska, where she faced the furor of racism spurred by the war and worked to dismantle segregation policies. She then transferred to the University of Chicago School of Law. When she graduated, she wanted to move to Hawaii and practice law with her now-found husband. However, the Hawaiian bar found her ineligible due to her loss of territorial status as a result of an old law that dismissed residency specifically for women from territories, requiring them to assume the same territory of residence as their husbands. With her newly secured law degree, she sued the Hawaiian bar on the grounds that the law was unconstitutional and based on sexist ideals. The Attorney General of Hawaii agreed, and she was allowed to practice law as a resident of Hawaii. Patsy Mink went on to become the first Japanese-American woman to practice law in the state of Hawaii. Using this victory as momentum, Patsy Mink almost immediately flung herself into the world of politics at a time when women, let alone women of color, were an uncommon and often unwelcome sight. She persevered and advocated for herself and those who would follow in her now-beaten path.

“We self-righteously expect all others to admire us for our democracy and our traditions. We are so smug about our superiority, we fail to see our own glaring faults, such as prejudice and poverty amidst affluence,” said Patsy Mink. She founded the Oahu Young Democrats in 1954, and with this platform, she immediately began her campaign for Congresswoman. In 1962, she won her seat in the United States House of Representatives with the help of a volunteer campaign force. She used her power to usher in a new era of progressive reform on Capitol Hill, passing the Women’s Educational Equality Act to promote equal opportunities in education and Title IX, which declared that “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Thanks to her contributions to society, she paved the way for women like her to follow in her footsteps and fight for their rights.

On November 25, 1846, a force of nature was born. Carrie Nation’s name whispered across taverns like a specter of sobriety, a militant leader of the prohibition movement. While many women fought in the streets and marched to state legislatures, Carrie Nation took the fight to bars themselves and encouraged other women to do the same. Alone or with hymn-singing women, Nation would clothe herself in a stark black and white dress, with a bag full of “Smashers,” which were stones that she would throw at bar fixtures and liquor bottles, along with a hatchet that she would use to dismantle tables and shatter windows. In utter shock that a sixty-year-old woman charged into their bar, screaming bible verses and smashing bar tables, all the men could do was stare in awe. In her own words, she described herself as “a bulldog running along at the feet of Jesus, barking at what He doesn’t like.”

Throughout her crusade against alcoholism, Carrie Nation was arrested thirty times. Upon her release, she would produce and sell hatchet-related paraphernalia to pay her fines, as well as print and sell her self-published newsletter, The Smasher, and newspaper, The Hatchet. In these publications, she displayed her fiery manifestos exhibiting her passion for prohibition, as well as religious texts and biblical advice. Interestingly, she also posted several of her own accounts of the “hatchetations,” the name she came to call her crusades of sobriety. She gained notoriety across cities and saloons throughout the country to the point that in 1901, a Kansas judge barred them from the city under the penalty of a $500 fine, roughly $16,000 USD today accounting for inflation.

In 1911, Nation died in Leavenworth, Kansas while giving a speech. She suddenly collapsed, and her final words were “I have done what I could.” While prohibition had failed, the movement empowered women to pursue political avenues and provided much-needed momentum to the suffrage movement at a time when women were seen as second-class citizens and for one to protest was considered uncivilized. Nation rose above it all, and her work helped to inspire a generation of women and propagate their power for the good of the nation.

We as a society owe so much to these unsung heroes of history, to think that there are thousands more of these women yet to be discussed, far beyond the classic tales of Ameila Airheart, Madame curie, and Rosa Parks, and while their stories are in the own rights important, since when did the history of important men stop at the founding fathers? We must never forget those to which we owe our lives.